Nodding syndrome was first noticed in Uganda in the late nineties, at the peak of clashes between the Lord's Resistance Army and government forces in Northern Uganda. Nodding syndrome has subsequently been reported in all the eight districts that make up the Acholi sub-region.

Despite earlier progress such as food relief to affected families and research response teams dispatched to find out the actual cause of the syndrome, these interventions by government and its partners were disrupted as a result of a diversion of resources and attention towards containing the pandemic occasioned by COVID-19.

The emergency inflicted on Uganda by the pandemic has in the past two years diverted attention from the plight of people living with the nodding syndrome.

While the pandemic plunged many people into financial instability and a spike in cases of domestic and sexual violence, these were already prevalent challenges for people living with nodding syndrome. The pandemic and subsequent lockdowns only compounded their battles and struggle to survive.

Ayeno Agnes, 19, has lived with the nodding syndrome since she was ten years old. She is passionate about learning but her condition has affected her ability to memorise the things she is taught.

For the past three years, Ayeno has been attending the same Primary Seven class at Alune Primary School in Laboromo village, Akwang sub-county, Kitgum district.

Ayeno at the borehole where she goes to drink some water in place of a meal at lunch.

Whenever the time for the Primary Leaving Examinations comes around, her teachers discourage her from sitting the exams because they believe she will even forget how to write her own name. However, in her mind, Ayeno is convinced that she is making progress.

According to a health worker at Kitgum Health Centre III where most of the patients receive treatment, nodding syndrome incapacitates and affects the capacity of its victims to learn and recall concepts.

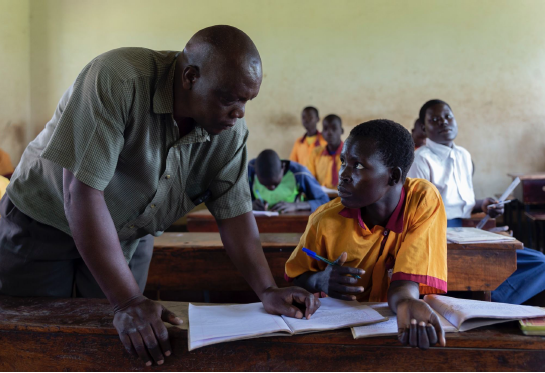

Kilama Patrick, 46, the Primary Seven class teacher at Alune Primary School where Ayeno has been studying, says she is actually able to remember things which are taught to her in repeated patterns on days when she is well fed. However, the challenge comes when she is starved for long hours as the school does not feed the students.

Kilama Patrick, 46 instructing Ayeno in class at Alune Primary School in Laboromo.

“I believe this girl can perform excellently in hand work because her brain is able to master repeated patterns,” Kilama says.

Kilama recommends supporting children with nodding syndrome to develop their hand work skills. “This girl is able to work in the garden, sell the produce and save her own money to buy uniforms and books. I believe she is brilliant, she just needs the right environment and support.”

Students at Alune Primary School, which has enrolled more than 40 pupils with nodding syndrome, report to school at 8am and study until 4pm with no meals in between. While starvation tends to trigger aggression from victims of the nodding syndrome, the school cannot afford to feed all the learners and teachers.

Aciro Jane, 49, a teacher, says the biggest problem faced by nodding syndrome victims, both boys and girls, is the lack of food both at home and at school. “There is no food in the community and when these children are hungry, they are very wild. They want to fight all the time and can not even play with their colleagues.”

Aciro adds that once hungry, children with nodding syndrome either become aggressive, sleepy or suffer convulsions and fall to the ground with saliva drooling out of their mouth.

Tooyelo Owisho Jamaica, 50, also a teacher at Alune Primary School, adds that poor nutrition and long hours of starvation aggravate the memory problem. “The children forget what they learn immediately. We just promote them to the next class to avoid aggression” which is usually their default reaction in face of any opposition.

Onama Charles, 49, the Paramount Chief of Pajim Akwang, says unstable memory is a grave problem for the girls because sometimes people take advantage to rape them without fear of getting caught as the victims won’t be able to recall the events clearly. “Most of the girls are raped during episodes of convulsion,” adds Onama, who said that the victims tend to lose consciousness during such episodes.

Mr. Onama Charles, the Paramount Chief of Pajim Akwang sub county.

It is usually under such circumstances that girls get sexually abused, he explains. He adds that the convulsions last anywhere between 10 minutes and a whole day, which is more than enough time for anyone to take advantage of a helpless victim.

In a bid to fight this menace, Onama has resorted to speaking against the rape of nodding syndrome victims as a form of advocacy during community engagements such as funerals and village meetings where he has to address people as a Paramount Chief.

Onama is also disappointed with the Central government, which he says sent people over to their village to collect blood samples but have never returned to give feedback on findings. He has now come to believe that maybe the problem is more spiritual than can be scientifically explained. “The parents have to take care of these children like babies because they can not be left on their own. The attacks strike anytime, even when the victims are eating or cooking.”

Abalo Vicky, 25, carries disfiguring scars on her face. She suffered an attack while she was cooking and fell right into the fire. Perhaps traumatised by the incident, her father has since discontinued Abalo’s education. Abalo’s father is of the view that it does not make sense for her to continue school when she won’t only be able to recall anything, but she will also get picked on and discriminated be her peers.

Abalo Vicky, 25 and her four year old son in Laboromo village, Akwang sub-county.

Regardless of her desire to continue with education, she cannot afford to pursue it without the support of her family. Now a mother of a four year old with an absentee lover because of her condition, Abalo’s fallback job is to learn tailoring. "I have not had the chance to try sowing, but I believe I can do it," Abalo affirms.

Otto Joe, 64, who is credited with reporting the first case of nodding syndrome to authorities in 1998, is saddened by the waning response to the plight of children living with nodding syndrome who are now becoming young parents.

He met the first victims of the condition during his routine visits as a village health volunteer in Tumangu village. Even when he reported the strange ailment, it was a while and many cases later, before his index report elicited an official response. He sees elements of the same apathy continue. He finds it incomprehensible that 24 years later, not even the cause of the syndrome has been established by scientists.

Currently living in Bajaere village, Labongo Akwang sub-county, in the Kitgum district, Otto now keeps a record of both new and old cases of nodding syndrome in his sub-county. He updates the lists based on information received from locals who report new cases of infection and deaths to him on a rolling basis. The record is also a disturbing catalog of the hundreds of female nodding syndrome victims who have suffered rape that is often perpetrated by close family members.

While appearing on NTV Uganda on April 12th, 2019, paediatric neurologist Dr Richard Idro said nodding syndrome is linked to the filarial worm which is spread through bites by black fleas. Dr Idro was part of a scientific research program on nodding syndrome from 2015, led by Dr Alfred Mubangizi who is the current Ag. Assistant Commissioner Vector Borne and Neglected Tropical Diseases at the Ministry of Health in Uganda. While it has been documented and reported that by 2019, over 3000 children had been affected by the nodding syndrome epidemic in northern Uganda, with an estimated case fatality rate of 6.7%, Dr Alfred is on record for declaring that there had been no new cases in the region from 2014 to-2019.

However, Otto’s records from 2018 to 2022, indicate otherwise.

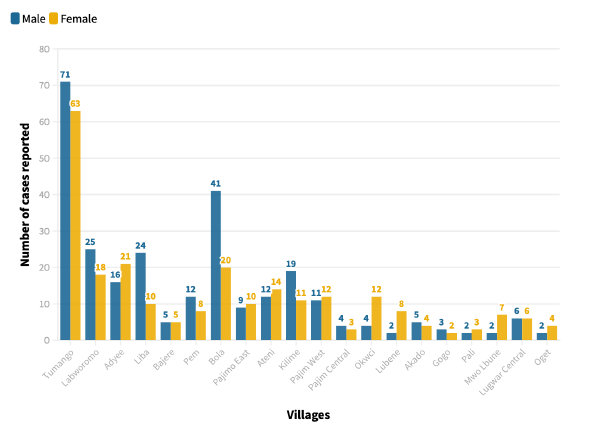

Below is a summary graph of the current 517 active cases of nodding syndrome in only 12 of the 40 villages of Labong Akwang sub-county, as per data received by the village health team volunteer; Otto Joe from 2018 to 2022. It should be noted that Labong Akwang is only one out of ten sub-counties that constitute the Kitgum district.

From the graph, it is evident that nodding disease syndrome cases are slightly higher among males than females, although, girls are more vulnerable in the face of sexual abuse when under attack.

While Otto’s records do not indicate specific dates when the cases were reported and recorded, he affirms the fact that the pandemic worsened the already prevalent challenges of hunger and the stigmatisation of victims resulting in abuse of their rights.

Otto Andrew, the District Health Officer (DHO) of Kitgum District, agrees that indeed there has been a funding gap between the years between 2019 and 2022. But he doubts the numbers in Otto Joe’s records. The DHO suspects that the VHTs are creating alarming statistics in order to attract food relief as the area is currently suffering from hunger due to prolonged dry spells in the Northern region. He insists, "Kitgum District has a cumulative total of 5,444 cases and we have not registered any new cases since 2014.”

Lakiri Eric, 54, and his wife Aculu Ventorina, 58, are parents to eight children, two of whom are boys who have lived with the nodding syndrome for the past over 14 years.

Kibwara Johnson, 23, caught the disease at seven years old and his brother Omachi Alfred, became victim of the same at five years old.

Omachi Alfred (21 years), supported by his father, Lakiri Eric (54) at their home in Labong Akwang, Kitgum district.

Due to prolonged periods without treatment, Omachi later developed a disability that crippled his legs when he turned 15. He is now unable to walk, eat, bathe or go to the toilet unassisted.

Both Omachi Alfred and his older brother Kibwara Johnson were forced to drop out of school at an early age. The District Health Commissioner says the government has had various interventions for families affected by the nodding syndrome. However, he recommends regular engagement and counselling for both the victims of nodding syndrome and their families. "This is a chronic problem that requires continuous presence on ground," says Andrew Otto, the DHO Kitgum District.

He notes that those who have been regular with taking their medication have improved and gotten back to work and school. However, hunger poses a big threat to their survival as even the absence of sugar in the body alone, can trigger a nodding syndrome attack.